Good Money, Inc., is a financial technology, or fintech, online digital banking platform, founded in 2018, that directs half of its profits to what it deems social justice and environmental initiatives. Their customers potentially get equity in the company when opening an account and can purportedly build on it through use of the “neobank’s” services. Unfortunately, their ex-general counsel decided to engage in illicit transactions defrauding the company of over $500,000. Proper due diligence and a robust risk and compliance program could have mitigated what occurred. These details reveal Good Money’s vulnerability and risk to investors and clients, but also teach not only how they can protect themselves going forward, but how other companies (and their clients) can learn how to better safeguard themselves.

On July 29, 2021, Brooke Campbell Solis was charged with six counts of wire fraud, in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1343. Solis pleaded guilty to all six counts.

Solis was General Counsel and later Chief Business Officer for Good Money from January 2018 to July 2019. She was barred in the state of California and telecommuted regularly from her home in Austin, Texas to Good Money’s San Francisco, CA home office.

During her time at Good Money, she diverted funds to shell companies and entities, she and her husband controlled. One such entity was a shell company named The Paralegal Group LLC, incorporated in Delaware, that she created and controlled and of which she was the sole member. One June 2, 2019, Solis entered into a consulting agreement between The Paralegal Group and Good Money and signed the agreement for both. She used the initials “R.D.” to sign on behalf of Paralegal Group LLC. Afterwards, Solis submitted an invoice from The Paralegal Group for $9,222.50. The invoice was dated May 31, 2019, 3 days before the consulting agreement was signed.

Solis also defrauded the company by charging them for personal expenses, including a $4,575 charge for a 61-day stay for her dogs at the dog boarding company “Jackson and Oliver boarding.” Solis admitted in the plea agreement that the dog boarding was her personal expense. According to an August 2020 FBI affidavit, the expense was submitted by Solis to her former employer on July 24, 2019 which Solis herself immediately approved, receiving the funds through another LLC she controlled. But Solis was no longer with Good Money on July 24, 2019. Her employment with them had been terminated two days earlier.

Her defrauding of Good Money did not end there. She continued on, diverting a minimum of $400,000 of Good Money’s funds into her personal checking account, almost two months after her departure from the company.

Why did an employee still have access to internal accounting systems at Good Money after she no longer worked there? And until close to two months later?

A criminal complaint (Case 3:20-mj-71196-MAG) was filed on August 26, 2020. In a March 14, 2022 court minute entry, (Case No. 3:21-cr-00297-JD-1), a federal judge sentenced Solis to 37 months in prison, followed by 3 years of supervised release and payment of $500,000 in restitution to Good Money. Solis also agreed to surrender her license to practice law as part of her plea agreement.

While Good Money is getting back $500,000 of the money it was defrauded and Brooke Campbell Solis is getting justice served, the effects on the company, its reputation, and clients is only beginning.

Reputation: Initial court records did not identify Brooke Campbell Solis’ employer as Good Money. It was however confirmed by Law.com through “other records, including an online video in which she promoted its services” that Good Money was Solis’ employer and the company was directly named in the March 14, 2020 court minute entry, (Case No. 3:21-cr-00297-JD-1). That the company name was withheld, was most likely an effort on the part of Good Money to control its reputational damage. But for Good Money’s clients and potential clients, embezzlement by a C-suite executive does not evoke a positive image, or inspire confidence that Good Money is being forthright with them. If a company has bad actors operating in their midst at such high levels, how does this reflect on the rest of their business? If they cannot keep their own money safe, how can they keep the money of their banking clients safe?

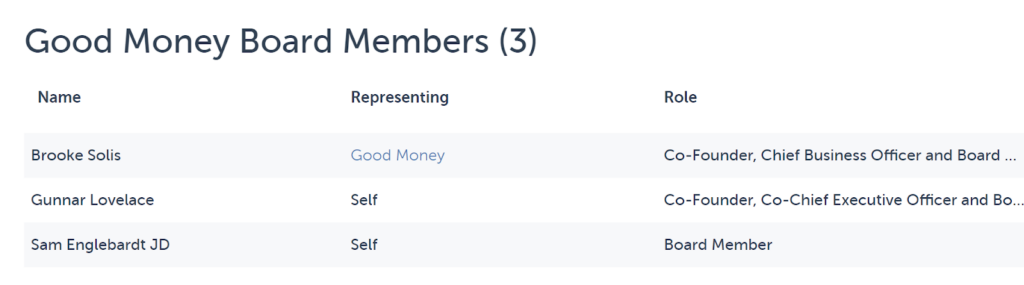

Less well known is the fact that Brooke Campbell Solis was not only General Counsel and then Chief Business Officer for Good Money, but also a co-founder of Good Money and a member of its 3-person board, according to PitchBook.

As a privately held company, Good Money can play their cards tighter to their vest, but it is important for a company to show both accountability and transparency. The Good Money website is sparse on information about the company. It contains no photos of management or specifics about their products. Their “Investor” link only goes to an email address and shows no actual investor information and the whole website is rendered in a strange Matrix green. Most information on what the company purportedly does is found in online articles rather than on the company’s website itself.

As seen in the Theranos case, it is important for a company to have industry experts on a company’s board or a separate body or subject matter expert consultants.

Along with the now convicted Solis, the two other board members consist of Gunnar Lovelace, founder of the online grocery store Thrive Market, who has no banking background and Sam Englebardt JD, an angel investor, whose experience as Vice President of Bernstein Global Wealth Management, a global asset management firm, is closer, but still a separate discipline. Another co-founder, Andrew Masanto has some experience as an investment banking analyst at Rothschild in Australia.

According to Crunch base, Good Money has 3 advisors: Ted Moskovitz, Matt McKibben, and Eli Broverman.

Broverman is no stranger to controversy. In 2018, Eli Boverman, one of the founding members and one-time president of the popular robo-advisor platform, Betterment, was, according to Forbes, “fined $400,000 by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) for a variety of alleged violations that took place between 2012 and 2015.” The allegations included violations of FINRA and SEC book and record keeping rules, non-compliance with the Customer Protection Rule, and window dressing.

Forbes further went on to point out: “While every new business experiences some growing pains, compliance seems to have been overlooked during these formative years for the company.” Without commenting on the ruling, Betterment accepted the fine. Betterment hired a new Chief Compliance Officer in August 2017.

This begs the question of why someone with this mark on their record could be hired in an advisory position? And what type of compliance program does Good Money have and who, if anyone, heads their compliance efforts?

This case leaves many important questions in its wake. Does Good Money have a compliance program or employ a compliance officer? If so, the embezzlement that occurred by a C-suite executive, after leaving the company, shows it has major flaws. Not to mention that her IT access should have been revoked immediately upon departure.

Does Good Money do regular executive background checks on its board, executives, advisors, and also critically, on the environmental and social justice companies it is putting money into?

It is important for any business to know who they are doing business with and who they are working with.

An executive background check performed by an independent and expert investigative firm could have uncovered important factors that could have alerted the company earlier regarding potential issues by Brooke Campbell Solis and could have advised on what measures to take. It was recommended in the March 14, 2022 court minute entry, (Case No. 3:21-cr-00297-JD-1) that Solis participate in a Residential Drug Abuse Program. It would be critical to know if Solis had a drug issue while acting as a C-suite executive and board member, not to mention someone who had “Super Administrative” access to internal accounting systems and managed legal, financial, and accounting practices while onboard.

It is easy to see how proper due diligence and a robust compliance and risk management program could have mitigated, or even prevented the embezzlement by its General Counsel. The best way to avoid a conflict of interest and prevent internal bias is having an external firm set up an industry appropriate compliance program that is tailored to that company’s setting.

Not everyone is who they say they are and situations and people can change. Statistics show that:

20% of executives have serious no-hire issues (hidden & undisclosed information)

35% of third-parties were found to have corruption related issues

75% of all criminal convictions, nationally, are missed by typical “state” and “nation-wide” searches conducted via typical “background checks.”

Going forward, Good Money needs to show that they have proper controls in place to protect themselves, their investors, and most importantly, their customers. Customers can learn to ask some hard questions before they invest their money in institutions that may not have the proper security and compliance controls in place. And companies can learn from Good Money’s scandal, why it is critical to implement a robust risk and compliance program and partner with an expert unbiased investigative firm that has the capabilities to set up a program that is right for them.